Fixing the issue in assumption of OLS step by step or one by one

Recent newsHi, I want to raise the issue related to know whether your OLS is ok or not.

read more(Comments)

Correlation coefficients are used to measure how strong a relationship is between two variables. There are several types of correlation coefficient, but the most popular is Pearson’s. Pearson’s correlation (also called Pearson’s R) is a correlation coefficient commonly used in linear regression. If you’re starting out in statistics, you’ll probably learn about Pearson’s R first. In fact, when anyone refers to the correlation coefficient, they are usually talking about Pearson’s.

Watch the video for an overview of the correlation coefficient, or read on below:

Can’t see the video? Click here.

Contents:

Correlation coefficient formulas are used to find how strong a relationship is between data. The formulas return a value between -1 and 1, where:

The absolute value of the correlation coefficient gives us the relationship strength. The larger the number, the stronger the relationship. For example, |-.75| = .75, which has a stronger relationship than .65.

Like the explanation? Check out the Practically Cheating Statistics Handbook, which has hundreds of step-by-step, worked out problems!

There are several types of correlation coefficient formulas.

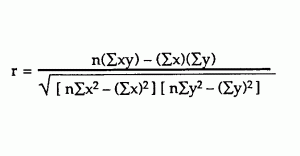

One of the most commonly used formulas is Pearson’s correlation coefficient formula. If you’re taking a basic stats class, this is the one you’ll probably use:

Two other formulas are commonly used: the sample correlation coefficient and the population correlation coefficient.

![]()

Sx and sy are the sample standard deviations, and sxy is the sample covariance.

![]()

The population correlation coefficient uses σx and σy as the population standard deviations, and σxy as the population covariance.

Check out my Youtube channel for more tips and help with statistics!

Correlation between sets of data is a measure of how well they are related. The most common measure of correlation in stats is the Pearson Correlation. The full name is the Pearson Product Moment Correlation (PPMC). It shows the linear relationship between two sets of data. In simple terms, it answers the question, Can I draw a line graph to represent the data? Two letters are used to represent the Pearson correlation: Greek letter rho (ρ) for a population and the letter “r” for a sample.

The PPMC is not able to tell the difference between dependent variables and independent variables. For example, if you are trying to find the correlation between a high calorie diet and diabetes, you might find a high correlation of .8. However, you could also get the same result with the variables switched around. In other words, you could say that diabetes causes a high calorie diet. That obviously makes no sense. Therefore, as a researcher you have to be aware of the data you are plugging in. In addition, the PPMC will not give you any information about the slope of the line; it only tells you whether there is a relationship.

Real Life Example

Pearson correlation is used in thousands of real life situations. For example, scientists in China wanted to know if there was a relationship between how weedy rice populations are different genetically. The goal was to find out the evolutionary potential of the rice. Pearson’s correlation between the two groups was analyzed. It showed a positive Pearson Product Moment correlation of between 0.783 and 0.895 for weedy rice populations. This figure is quite high, which suggested a fairly strong relationship.

If you’re interested in seeing more examples of PPMC, you can find several studies on the National Institute of Health’s Openi website, which shows result on studies as varied as breast cyst imaging to the role that carbohydrates play in weight loss.

Back to Top

Watch the video to learn how to find PPMC by hand.

Can’t see the video? Click here.

Example question: Find the value of the correlation coefficient from the following table:

| Subject | Age x | Glucose Level y |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 43 | 99 |

| 2 | 21 | 65 |

| 3 | 25 | 79 |

| 4 | 42 | 75 |

| 5 | 57 | 87 |

| 6 | 59 | 81 |

Step 1: Make a chart. Use the given data, and add three more columns: xy, x2, and y2.

| Subject | Age x | Glucose Level y | xy | x2 | y2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 43 | 99 | |||

| 2 | 21 | 65 | |||

| 3 | 25 | 79 | |||

| 4 | 42 | 75 | |||

| 5 | 57 | 87 | |||

| 6 | 59 | 81 |

Step 2: Multiply x and y together to fill the xy column. For example, row 1 would be 43 × 99 = 4,257.

| Subject | Age x | Glucose Level y | xy | x2 | y2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 43 | 99 | 4257 | ||

| 2 | 21 | 65 | 1365 | ||

| 3 | 25 | 79 | 1975 | ||

| 4 | 42 | 75 | 3150 | ||

| 5 | 57 | 87 | 4959 | ||

| 6 | 59 | 81 | 4779 |

Step 3: Take the square of the numbers in the x column, and put the result in the x2 column.

| Subject | Age x | Glucose Level y | xy | x2 | y2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 43 | 99 | 4257 | 1849 | |

| 2 | 21 | 65 | 1365 | 441 | |

| 3 | 25 | 79 | 1975 | 625 | |

| 4 | 42 | 75 | 3150 | 1764 | |

| 5 | 57 | 87 | 4959 | 3249 | |

| 6 | 59 | 81 | 4779 | 3481 |

Step 4: Take the square of the numbers in the y column, and put the result in the y2 column.

| Subject | Age x | Glucose Level y | xy | x2 | y2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 43 | 99 | 4257 | 1849 | 9801 |

| 2 | 21 | 65 | 1365 | 441 | 4225 |

| 3 | 25 | 79 | 1975 | 625 | 6241 |

| 4 | 42 | 75 | 3150 | 1764 | 5625 |

| 5 | 57 | 87 | 4959 | 3249 | 7569 |

| 6 | 59 | 81 | 4779 | 3481 | 6561 |

Step 5: Add up all of the numbers in the columns and put the result at the bottom of the column. The Greek letter sigma (Σ) is a short way of saying “sum of” or summation.

| Subject | Age x | Glucose Level y | xy | x2 | y2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 43 | 99 | 4257 | 1849 | 9801 |

| 2 | 21 | 65 | 1365 | 441 | 4225 |

| 3 | 25 | 79 | 1975 | 625 | 6241 |

| 4 | 42 | 75 | 3150 | 1764 | 5625 |

| 5 | 57 | 87 | 4959 | 3249 | 7569 |

| 6 | 59 | 81 | 4779 | 3481 | 6561 |

| Σ | 247 | 486 | 20485 | 11409 | 40022 |

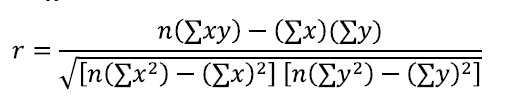

Step 6: Use the following correlation coefficient formula.

The answer is: 2868 / 5413.27 = 0.529809

Click here if you want easy, step-by-step instructions for solving this formula.

From our table:

The correlation coefficient =

= 0.5298

The range of the correlation coefficient is from -1 to 1. Our result is 0.5298 or 52.98%, which means the variables have a moderate positive correlation.

Back to Top.

Like the explanation? Check out the Practically Cheating Statistics Handbook, which has hundreds more step-by-step explanations, just like this one!

If you’re taking AP Statistics, you won’t actually have to work the correlation formula by hand. You’ll use your graphing calculator. Here’s how to find r on a TI83.

Step 1: Type your data into a list and make a scatter plot to ensure your variables are roughly correlated. In other words, look for a straight line. Not sure how to do this? See: TI 83 Scatter plot.

Step 2: Press the STAT button.

Step 3: Scroll right to the CALC menu.

Step 4: Scroll down to 4:LinReg(ax+b), then press ENTER. The output will show “r” at the very bottom of the list.

Tip: If you don’t see r, turn Diagnostic ON, then perform the steps again.

Watch the video:

Can’t see the video? Click here.

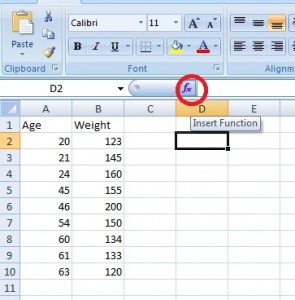

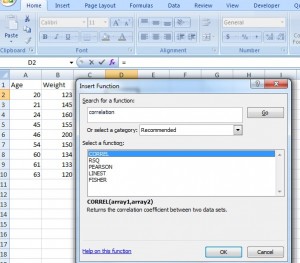

Step 1: Type your data into two columns in Excel. For example, type your “x” data into column A and your “y” data into column B.

Step 2: Select any empty cell.

Step 3: Click the function button on the ribbon.

Step 4: Type “correlation” into the ‘Search for a function’ box.

Step 5: Click “Go.” CORREL will be highlighted.

Step 6: Click “OK.”

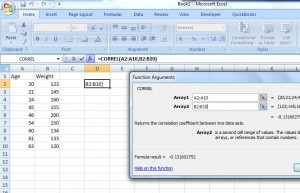

Step 7: Type the location of your data into the “Array 1” and “Array 2” boxes. For this example, type “A2:A10” into the Array 1 box and then type “B2:B10” into the Array 2 box.

Step 8: Click “OK.” The result will appear in the cell you selected in Step 2. For this particular data set, the correlation coefficient(r) is -0.1316.

Caution: The results for this test can be misleading unless you have made a scatter plot first to ensure your data roughly fits a straight line. The correlation coefficient in Excel 2007 will always return a value, even if your data is something other than linear (i.e. the data fits an exponential model).

That’s it!

Subscribe to our Youtube Channel for more Excel tips and stats help.

Back to top.

Watch the video for the steps:

Can’t see the video? Click here.

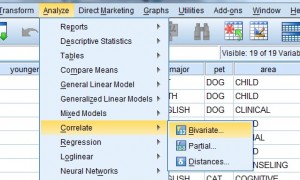

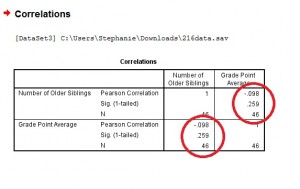

Step 1: Click “Analyze,” then click “Correlate,” then click “Bivariate.” The Bivariate Correlations window will appear.

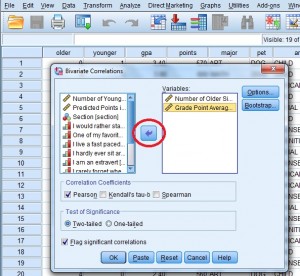

Step 2: Click one of the variables in the left-hand window of the Bivariate Correlations pop-up window. Then click the center arrow to move the variable to the “Variables:” window. Repeat this for a second variable.

Step 3: Click the “Pearson” check box if it isn’t already checked. Then click either a “one-tailed” or “two-tailed” test radio button. If you aren’t sure if your test is one-tailed or two-tailed, see: Is it a a one-tailed test or two-tailed test?

Step 4: Click “OK” and read the results. Each box in the output gives you a correlation between two variables. For example, the PPMC for Number of older siblings and GPA is -.098, which means practically no correlation. You can find this information in two places in the output. Why? This cross-referencing columns and rows is very useful when you are comparing PPMCs for dozens of variables.

Tip #1: It’s always a good idea to make an SPSS scatter plot of your data set before you perform this test. That’s because SPSS will always give you some kind of answer and will assume that the data is linearly related. If you have data that might be better suited to another correlation (for example, exponentially related data) then SPSS will still run Pearson’s for you and you might get misleading results.

Tip #2: Click on the “Options” button in the Bivariate Correlations window if you want to include descriptive statistics like the mean and standard deviation.

Back to top.

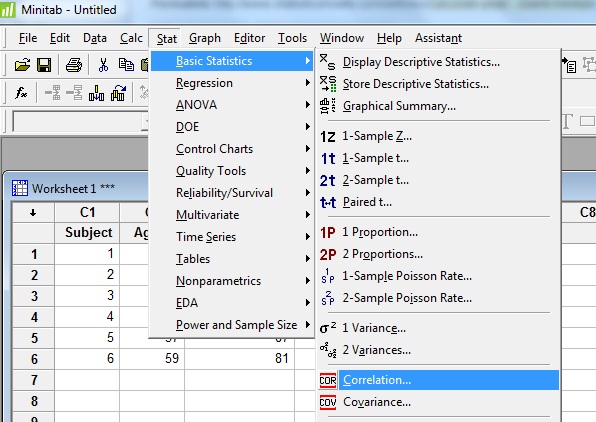

Watch this video on how to calculate the correlation coefficient in Minitab:

Can’t see the video? Click here.

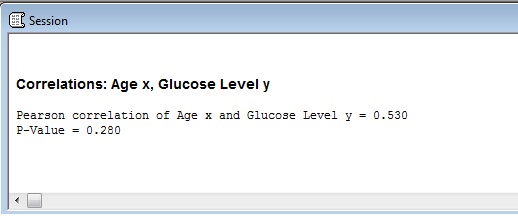

The Minitab correlation coefficient will return a value for r from -1 to 1.

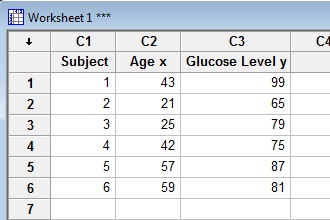

Example question: Find the Minitab correlation coefficient based on age vs. glucose level from the following table from a pre-diabetic study of 6 participants:

| Subject | Age x | Glucose Level y |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 43 | 99 |

| 2 | 21 | 65 |

| 3 | 25 | 79 |

| 4 | 42 | 75 |

| 5 | 57 | 87 |

| 6 | 59 | 81 |

Step 1: Type your data into a Minitab worksheet. I entered this sample data into three columns.

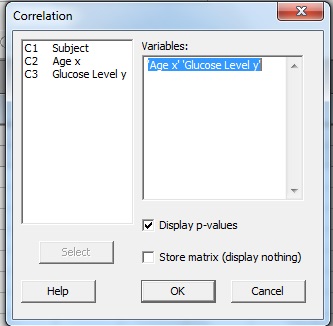

Step 2: Click “Stat”, then click “Basic Statistics” and then click “Correlation.”

Step 3: Click a variable name in the left window and then click the “Select” button to move the variable name to the Variable box. For this example question, click “Age,” then click “Select,” then click “Glucose Level” then click “Select” to transfer both variables to the Variable window.

Step 4: (Optional) Check the “P-Value” box if you want to display a P-Value for r.

Step 5: Click “OK”. The Minitab correlation coefficient will be displayed in the Session Window. If you don’t see the results, click “Window” and then click “Tile.” The Session window should appear.

For this dataset:

That’s it!

Tip: Give your columns meaningful names (in the first row of the column, right under C1, C2 etc.). That way, when it comes to choosing variable names in Step 3, you’ll easily see what it is you are trying to choose. This becomes especially important when you have dozens of columns of variables in a data sheet!

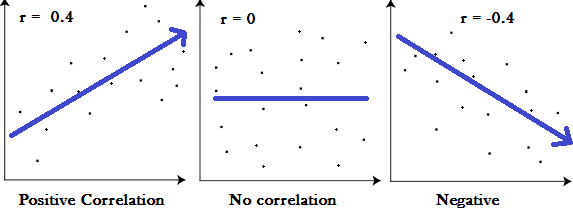

Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient is a linear correlation coefficient that returns a value of between -1 and +1. A -1 means there is a strong negative correlation and +1 means that there is a strong positive correlation. A 0 means that there is no correlation (this is also called zero correlation).

This can initially be a little hard to wrap your head around (who likes to deal with negative numbers?). The Political Science Department at Quinnipiac University posted this useful list of the meaning of Pearson’s Correlation coefficients. They note that these are “crude estimates” for interpreting strengths of correlations using Pearson’s Correlation:

| r value = | |

| +.70 or higher | Very strong positive relationship |

| +.40 to +.69 | Strong positive relationship |

| +.30 to +.39 | Moderate positive relationship |

| +.20 to +.29 | weak positive relationship |

| +.01 to +.19 | No or negligible relationship |

| 0 | No relationship [zero correlation] |

| -.01 to -.19 | No or negligible relationship |

| -.20 to -.29 | weak negative relationship |

| -.30 to -.39 | Moderate negative relationship |

| -.40 to -.69 | Strong negative relationship |

| -.70 or higher | Very strong negative relationship |

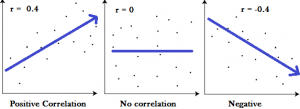

It may be helpful to see graphically what these correlations look like:

The images show that a strong negative correlation means that the graph has a downward slope from left to right: as the x-values increase, the y-values get smaller. A strong positive correlation means that the graph has an upward slope from left to right: as the x-values increase, the y-values get larger.

Back to top.

Cramer’s V Correlation is similar to the Pearson Correlation coefficient. While the Pearson correlation is used to test the strength of linear relationships, Cramer’s V is used to calculate correlation in tables with more than 2 x 2 columns and rows. Cramer’s V correlation varies between 0 and 1. A value close to 0 means that there is very little association between the variables. A Cramer’s V of close to 1 indicates a very strong association.

| Cramer’s V | |

| .25 or higher | Very strong relationship |

| .15 to .25 | Strong relationship |

| .11 to .15 | Moderate relationship |

| .06 to .10 | weak relationship |

| .01 to .05 | No or negligible relationship |

A correlation coefficient gives you an idea of how well data fits a line or curve. Pearson wasn’t the original inventor of the term correlation but his use of it became one of the most popular ways to measure correlation.

Francis Galton (who was also involved with the development of the interquartile range) was the first person to measure correlation, originally termed “co-relation,” which actually makes sense considering you’re studying the relationship between a couple of different variables. In Co-Relations and Their Measurement, he said

“The statures of kinsmen are co-related variables; thus, the stature of the father is correlated to that of the adult son,..and so on; but the index of co-relation … is different in the different cases.”

It’s worth noting though that Galton mentioned in his paper that he had borrowed the term from biology, where “Co-relation and correlation of structure” was being used but until the time of his paper it hadn’t been properly defined.

In 1892, British statistician Francis Ysidro Edgeworth published a paper called “Correlated Averages,” Philosophical Magazine, 5th Series, 34, 190-204 where he used the term “Coefficient of Correlation.” It wasn’t until 1896 that British mathematician Karl Pearson used “Coefficient of Correlation” in two papers: Contributions to the Mathematical Theory of Evolution and Mathematical Contributions to the Theory of Evolution. III. Regression, Heredity and Panmixia. It was the second paper that introduced the Pearson product-moment correlation formula for estimating correlation.

If you can read a table — you can test for correlation coefficient. Note that correlations should only be calculated for an entire range of data. If you restrict the range, r will be weakened.

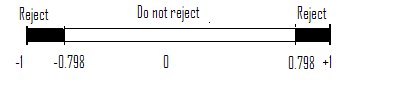

Sample problem: test the significance of the correlation coefficient r = 0.565 using the critical values for PPMC table. Test at α = 0.01 for a sample size of 9.

Step 1: Subtract two from the sample size to get df, degrees of freedom.

9 – 7 = 2

Step 2: Look the values up in the PPMC Table. With df = 7 and α = 0.01, the table value is = 0.798

Step 3: Draw a graph, so you can more easily see the relationship.

r = 0.565 does not fall into the rejection region (above 0.798), so there isn’t enough evidence to state a strong linear relationship exists in the data.

It’s rare to use trigonometry in statistics (you’ll never need to find the derivative of tan(x) for example!), but the relationship between correlation and cosine is an exception. Correlation can be expressed in terms of angles:

More specifically, correlation is the cosine of an angle between two vectors defined as follows (Knill, 2011):

If X, Y are two random variables with zero mean, then the covariance Cov[XY] = E[X · Y] is the dot product of X and Y. The standard deviation of X is the length of X.

Acton, F. S. Analysis of Straight-Line Data. New York: Dover, 1966.

Edwards, A. L. “The Correlation Coefficient.” Ch. 4 in An Introduction to Linear Regression and Correlation. San Francisco, CA: W. H. Freeman, pp. 33-46, 1976.

Gonick, L. and Smith, W. “Regression.” Ch. 11 in The Cartoon Guide to Statistics. New York: Harper Perennial, pp. 187-210, 1993.

Knill, O. (2011). Lecture 12: Correlation. Retrieved April 16, 2021 from: http://people.math.harvard.edu/~knill/teaching/math19b_2011/handouts/lecture12.pdf

Hi, I want to raise the issue related to know whether your OLS is ok or not.

read moreThe **45-degree line** in economics and geometry refers to a line where the values on the x-axis and y-axis are equal at every point. It typically has a slope of 1, meaning that for every unit increase along the horizontal axis (x), there is an equal unit increase along the vertical axis (y). Here are a couple of contexts where the 45-degree line is significant:

read moreThe **hyperinflation in Hungary** in the aftermath of World War II (1945–1946) is considered the worst case of hyperinflation in recorded history. The reasons behind this extreme economic event are numerous, involving a combination of war-related devastation, political instability, massive fiscal imbalances, and mismanagement of monetary policy. Here's an in-depth look at the primary causes:

read more**Neutrality of money** is a concept in economics that suggests changes in the **money supply** only affect **nominal variables** (like prices, wages, and exchange rates) and have **no effect on real variables** (like real GDP, employment, or real consumption) in the **long run**.

read moreDeflation in Japan, which has persisted over several decades since the early 1990s, is a complex economic phenomenon. It has been influenced by a combination of structural, demographic, monetary, and fiscal factors. Here are the key reasons why deflation occurred and persisted in Japan:

read moreHedging against inflation involves taking financial or investment actions designed to protect the purchasing power of money in the face of rising prices. Inflation erodes the value of currency over time, so investors seek assets or strategies that tend to increase in value or generate returns that outpace inflation. Below are several ways to hedge against inflation:

read moreThe **Phillips Curve** illustrates the relationship between inflation and unemployment, and how this relationship differs in the **short run** and the **long run**. Over time, economists have modified the original Phillips Curve framework to reflect more nuanced understandings of inflation and unemployment dynamics.

read moreDealing with inflation requires a combination of **fiscal and monetary policy** tools. Policymakers adjust these tools depending on the nature of inflation—whether it's **demand-pull** (inflation caused by excessive demand in the economy) or **cost-push** (inflation caused by rising production costs). Below are key approaches to controlling inflation through fiscal and monetary policy.

read more

Collaboratively administrate empowered markets via plug-and-play networks. Dynamically procrastinate B2C users after installed base benefits. Dramatically visualize customer directed convergence without

Comments